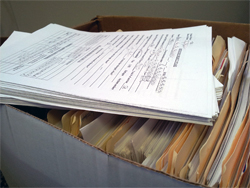

When my colleagues and I visit immigration detention centers to do Know Your Rights presentations and conduct legal intake, we are not able to bring computers with us. As result, the tangible outcome of any Know Your Rights visit is a stack of handwritten intake worksheets prepared by us and our partners and volunteers. Once we get back to the office, the supervising attorney of the detention project sets to work reviewing each of these worksheets to screen each person’s case for possible immigration relief. After this flurry of activity, a stack of handwritten worksheets remain. The next, somewhat anticlimactic, task is to enter the information from each case into our database.

Although this data entry is one of the more menial tasks around our office, it is one of the hardest. Every time I spend an hour inputting these intakes to our database, I’m overwhelmed by the sheer magnitude of the problem. Although at that point the case is, to me, a worksheet, I know that each worksheet represents a person with a story. These stories are told in the notes taken by the intake workers, often distressingly similar: “Worried about his kids,” “Only support for his kids and doesn’t know what will happen to them,” “Family losing their home without him, worried about his kids.” Detainees often will mention that they are the main caregiver or are working to help pay for the medical care for a sick family member. For many of them, detention and deportation compound hardships their families already are experiencing – for example, a spouse who is going through a high risk pregnancy or who has recently been laid off.

A lucky few of these people will be able to apply for a chance to remain in the United States, if they meet all of the requirements to apply for a form of immigration relief. Many will fall just short of eligibility due to some detail: they have been in the United States only eight or nine years instead of ten, or they went to visit family out of the country at the wrong time and incurred a bar, or they have a minor criminal conviction from many years ago, regardless of any rehabilitation or other mitigating factors surrounding that conviction. If an individual does not meet all the requirements, an immigration judge cannot do anything for that person no matter how sympathetic the case may be or how badly the judge may feel about it. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) technically can exercise discretion in these cases, but as we have seen this happens relatively rarely.

According to DHS, 392,000 people were deported in fiscal year 2011. While DHS would have us believe they were “criminal aliens” who were threatening our communities, the reality is much less black and white. Many do not have criminal convictions more serious than driving-related offenses, and many of those who do have other convictions, such as drug possession or shop lifting, are far from being a threat. Often these offenses were one-time occurrences and happened many years ago. Serious convictions are few and far between. Yet in our frenzy to deport record numbers of people jails are kept full and a trail of broken and impoverished families is left in the wake. Whatever these people may have done wrong does not change the fact that their deportations are a serious threat to the integrity of our communities.

After being processed through a system that allows very little room for concern about their personal circumstances, after becoming a statistic in the eyes of the DHS and the world, what remains are the stories that we hear at the detention centers, scribble on the backs of intake sheets, and bear witness to as best we can. While I sometimes feel overwhelmed by these stories, I am happy to do what I can to make sure they are not forgotten.

Elizabeth Kalmbach is the detention and due process coordinator for Heartland Alliance’s National Immigrant Justice Center, where she organizes Know Your Rights visits and provides legal consultations to immigrants detained at six county jails in Illinois, Wisconsin, and Kentucky.

NIJC has a new Chicago address at 111 W. Jackson Blvd, Suite 800, Chicago, IL 60604 and a new email domain at @immigrantjustice.org.